In a previous post, I suggested ideas for how a coach may properly utilize the one minute break to refocus his/her fencer and provide tactical recommendations to either turn the tables or maintain a lead.

At the recommendation of my colleagues at The Fencing Coach: Leland “The Dark Lord of Canada” Guillemin, and Hannah Provenza, I hope to address how an athlete may approach the one minute break should they not have a coach present.

In fencing, the one minute break is far more than an opportunity for the athlete to catch their breath (though in recent memory, I’ve needed the one minute break to do just that!). It is time for reflection; it is time to regroup, and a time to strategize for the period ahead.

Whether winning or losing, the simple act of disengaging oneself from the bout to collect one’s thoughts can have monumental benefits in the subsequent periods. For experienced fencers, this personal reflection can be even more advantageous than having a strip coach to discuss strategy with.

During the 2013 World Championships, Miles Chamley-Watson entered the second break with a 11-3 deficit to Sebastien Bachmann. Rather than summon his coach Simon Gershon for advice, Chamley-Watson simply closed his eyes, took a deep breath, focused, and strategized for the period ahead. Despite his eight touch deficit and Bachmann being only four touches from victory, Chamley-Watson believed that he could turn the tables on the German and win.

When recounting the strategic change in my interview with him, Chamley-Watson noted that “…I changed my game so I would be more stubborn in my approach and preparation. Each time I attacked him, it simply did not work. I decided I would start attacking him with the intention of picking up the blade in opposition which I had anticipated being the safest route to mounting a comeback. This gave me enough time to judge the distance, which was the difference in the match.”

Chamley-Watson’s articulation of his strategy is noteworthy for three reasons:

- He had a self-awareness for what was not working and what put him down eight touches. (Failure in approach and preparation)

- He understood what was in his repertoire and how he could use this to change the course of the bout. (Greater distance, intent to take Bachmann’s blade in opposition)

- He never believed the bout was out of his reach. “Mentally,” Chamley-Watson said, “always tell yourself that it is never over until those seconds end.”

The story is well known. Chamley-Watson came back on Bachmann, won 15-14, and ultimately went on to become the 2013 Men’s Foil World Champion.

Your coach isn’t going to be there with you for every tournament, and even if s/he is, the journey of the bout is sometimes best taken alone. Adjustments must be made from touch-to-touch, but the true strategic changes come during the one minute break.

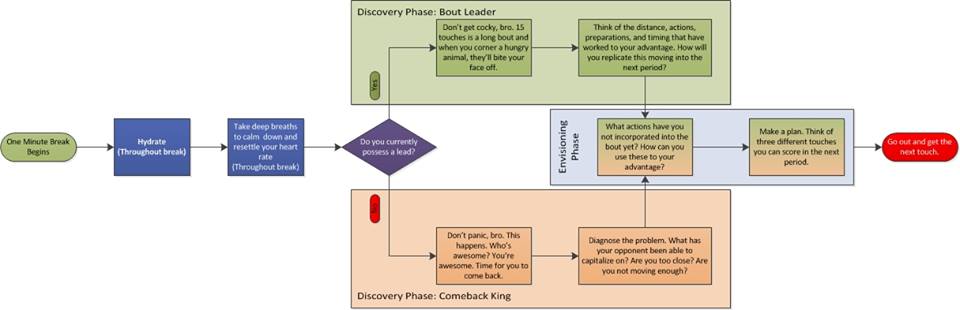

With input from my colleagues at The Fencing Coach, we’ve designed the following diagram to help visualize how to best make use of the one minute break.

Remember, the bout is neither over if you’re winning nor losing. It is only over when, as Miles said, the final seconds tick away. Use that one minute break to position yourself for maximum success.

Talk Back: How do you use the one minute break to your advantage when you don’t have your coach present?

“I know it’s only somewhat related, but during college fencing bouts whenever the other team called a timeout in a bout I was fencing, rather than coaching or anything I encouraged my whole team to line up for hugs. I don’t know if it was the hugs, but I never went on to lose a bout that I was winning because the other team called a timeout. It was probably the hugs, actually.” – Ben White

“Jaeger Bombs!” – Aaron Hambleton

“Turn my back on my opponent, take deep breaths, drink my electrolyte water and think….rationally.” – Richmond Fencing Club Head Coach Cyndi Lucente

“Yell at myself in Bulgarian.” – Brandeis University Fencer Ari Feingersch

“The main thing I do when my coach is absent, is start to panic (prior to the break). That being said, as soon as the break starts, i’m working on controlling my breathing in-between drinking some water. That allows me to calm down and look at the other fencer as well as what i’m doing with a more controlled eye, allowing me to make necessary changes.” – Maccabi Team Member Andrew Bogetz

“Focus on facts and develop a plan from there. Normal questions I ask myself are: “What were the last 5 actions?” “What action was behind each of my points?” “What action did he use for each point?” “In both cases, does one action occur more than the others?” “What actions have I not tried?” “Physically WHERE on the strip has each touch occured? My side? His? In the box?” –Capitol Fencing Academy Assistant Coach Litteton Riggins

“Adjustments. Always about adjustments, whether you’re winning or losing. If you’re winning, how will they adjust to what you’re doing to beat them? The next point is about establishing the remainder of the bout. If I’m winning, my next point is something they haven’t seen me do yet, good or bad. Once they think you’re doing something else, go back to what was working as they will forget what they thought about at the break.” – Chad Short