Last week, I briefly touched on the importance of YouTube and how watching it religiously could make tangible improvements to your fencing career. I wrote:

“YouTube is such a valuable asset to your training and preparation for a tournament. The upcoming 2014 World Championships in Kazan will be streamed live on the FIE’s YouTube Channel, and should be viewed by every fencer aspiring to greatness. Spending at least an hour of week watching videos on YouTube can help you digest a variety of things:

- YouTube helps you understand trends in global fencing and recognize how to apply these trends to your game.

- YouTube provides a means to scout your potential opponents and be a step ahead of them when you go toe-to-toe on the piste.

- YouTube helps you understand tactics and distance at an advanced level. In studying tactics and what others are doing, you can emulate this behavior in your bouts and truly play the game of physical chess.”

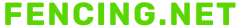

This week, I wanted to write an expanded post to help you understand how to watch it—specifically, how tempo, distance, preparation, and strategy work together to earn touches, and how to watch for these moving parts.

Leading up to the 2013 Maccabi Games, I knew that Israel would be sending World Champion Yuval Freilich to the event, and I wanted an opportunity to give my best bout against him. Freilich was, and continues to be an amazing fencer with few holes in his game. I knew that because of his physical superiority, better form, and the fact that he had a larger repertoire than I, the only way I would be able to defeat him was using my brain. As the games approached I would spend hours every week watching every bout of his I could find, analyzing every touch he scored, every touch scored against him, and tried to find common themes in tempo, preparations, and footwork that I could replicate on the strip if we went toe-to-toe. I creepily stalked him on the YouTube interwebs like a walking SafeSport violation.

By the time we fenced, I felt like I was matching up against an old, familiar opponent. I knew the tempo to fence at the start; I knew when to change it. I knew how and where to prepare, I knew when to push him, and when to let him come to me. I knew to continuously move the blade because he loved closing out in 4. By the end of the bout, I walked away with a 13-6 victory—a result that was 100% attributable to preparation on YouTube.

With the 2014 World Championships in Kazan beginning this week, now’s a good time to start learning how to watch and analyze fencing on YouTube if you don’t know already. Besides the benefits I listed above, if you learn to watch a bout in depth and understand what’s going on, it will make you a better fencer, as well as a better strip coach. I hope you’ll find this guide useful!

Tempo- The first thing to watch for as you observe YouTube is tempo. While “tempo” is a wide reaching concept with many definitions, let us define it, for this sake, as the rate of movement of the fencer/s. Using the 2012 NCAA Men’s Epee Final between Alen Hadzic and Jonathan Yergler as an example, if we observe this bout from a tempo perspective, we see two fencers with very different rates of movement; Yergler with a traditional feet on the ground, small step approach to his game versus Hadzic’s balls of the feet higher rate of movement style. Stylistically, this contrast of tempos benefited Yergler, who was able to feel Alen’s timing as he came forward and often times, catch Alen standing up and unready.

Elite level fencers will be able to adjust their tempos on the go as the bout dictates. For a bout that demonstrated at least four or five tempo changes from both fencers, observe the following bout in Stockholm between Max Heinzer and Olympic Silver Medalist Jin Jung. Both fencers begin the bout fencing at an extremely fast tempo, yet once each realizes that the tempo is backfiring in such a way that his opponent is able to strike into the other’s prep, the steps get smaller, the tip more compact, and at 14-14 after many adjustments and subtle changes to the speed, Jung slips away by a hair.

Questions to ask about tempo as you watch YouTube: What is the rate of movement of the fencers? How does it change throughout the bout? How is the tempo benefiting or harming the fencer’s approach?

Preparation- Allen Evans of Coaches Compendium defines preparation as the use of the blade, the feet, or the use of the feet and the blade together to create windows of opportunity to score a touch. Your preparation itself can often lead to a touch, and if you understand your opponent’s tendencies in preparation, you can find the moment to strike in a state of unpreparedness. For our YouTube case study in preparation, let’s have a look at the 2011 World Championship Final in Catania between Paolo Pizzo (ITA) and Fabian Kauter (SUI). Pizzo is a master of making huge feints in preparation with the blade (particularly in 8 and 6), making his opponents react to the massive opening, and then using his quick hand to make them pay.

Here, we have a case of Pizzo dropping his hand in a swooping 8 in preparation.

Kauter responds with a lunge to the open hand…

And Pizzo flicks him over the top of the wrist as Kauter’s lunge comes out.

This touch is a perfect, simple example of how to watch for preparation. At another point in the bout, Pizzo attempts to prepare with the sweeping 8 once again.

But this time, Kauter knows how to capitalize on the preparation, and rather than go straight in and fall for the counter flick once again, Kauter surprises Pizzo by going under his hand, disrupting the preparation and earning a touch.

At the World Cup level, preparation is everything. Gauthier Grumier (FRA), is an excellent fencer to watch to gain a better understanding of how effective preparation around the hand rarely needs a finishing action to the body if you’re able to control the bout with the short targets. Focus on the preparation, and learn what the fencer is trying to do to open windows for a touch.

Questions to ask about preparation as you watch YouTube- How does the fencer like to prepare? How is the fencer leaving himself/herself open to attack in their preparation? How does the fencer change his/her preparations throughout the bout? How are they using their feet to prepare? How are they using their hand? How are they using their feet and hand together to prepare? Why do they call them breakfast treats if you can eat them at any time of day?

Distance- Explaining distance in the simplest terms, my coach Jon Normile defined distance in such a way that described it as “A distance,” “B distance,” and “C distance.” Think of C distance as the distance at which fencers line up en garde. If you attack from this range with a one tempo action, against a good fencer, you’re going to get pulverized with a counterattack or a swift parry-riposte.

Now close the distance with the opponent a little to roughly advance lunge distance, and you’re in “B distance,” where your tips are just starting to cross paths.

Next, you have what you call “A distance,” which I will also call the “do something or get the hell out distance.” Your tip is practically over your opponent’s bell-guard at this point. From this distance, there is a small window to either commit to the action you’ve set up or get out and try again. Staying in this distance too long is just as dangerous to you as it is your opponent. Among the best fencers, once they have closed distance to “A,” it is a matter of a split second before they have committed to the final action.

“A, B, and C” distances are of course a simplification, but a good starting framework to understand opponent positioning.

Using two-time World Champion Nikolai Novosjolov as an example, Novosjolov is a master of constantly applying pressure from within “B distance” and never allowing his opponents to get comfortable. The Fencing Coach editor Leland Guillemin did an excellent video analysis of Novosjolov’s tactics. Here, we have Novosjolov pressuring around Kauter’s guard at “B distance,”

Before a quick advance and feint is applied to close to “A distance,”

And the moment after Novosjolov feels the tip over the guard in “A distance,” Kauter reacts in six, allowing Novosjolov to disengage to the low-line as he closes to the body. When a fencer is in “A distance,” it becomes a kill or be killed moment.

Questions to ask about distance as you watch YouTube: What is/are the distances that each fencer is most comfortable in? What does the fencer do to deceive and close the distance?

Strategy- Fencing is a sport that has been called “Physical Chess” for a reason. Behind every movement of the hand and foot is (in theory) a motion that is preparing for a touch. In the highest echelons of competitive fencing, most bouts are decided only by one or two touches. This is partially due to constant strategy adjustments from high-level fencers who understand that you’re unlikely to hit your opponent the same way twice, and for the fencer who might be down, the understanding that “something’s got to change” if s/he is to rally back and recover lost points. Think of strategy as the point at which footwork, distance, preparation, and tempo work together to score touches.

As a case study in strategy adjustments, let us revisit the 2012 Milwaukee NAC Division I Men’s Epee Final between Soren Thompson and Jason Pryor. In the first two periods, Thompson relies primarily on his short game, wary of committing to a deep attack on Pryor, who managed to disrupt Thompson’s preparations with toe touches and wrist shots.

It is in the third period, down 6-3, Thompson makes a radical strategic adjustment, no longer playing for Pryor’s short targets, but closing deep.

Thompson ultimately brought the score to 10-10 before finding himself down 12-10 with 16 seconds remaining. But the fundamental strategic change is worth noting—keeping in mind that there is more complexity to “he committed deep,” but for the sake of this high level overview, we’ll keep it at that (you can read a deeper analysis by clicking on the link above).

By watching the same opponent multiple times via YouTube, you can gain a better understanding of how they think, how they maintain a lead when they’re up, what they go for when they’re down, and a general understanding of weaknesses.

Questions to ask about strategy as you watch on YouTube: How are the fencers making changes to their tempo to score touches? How are the fencers making changes to their distance? How are the fencers adjusting their preparatory actions?

As the World Championships kick off this week, use this as a guide to understand what’s going on. The more you do it, the better you’ll get as both a fencer and a coach!